I was not happy at Art School in the late ‘sixties. The obsession with then-current edge Abstract Expressionism did not interest me at all: I was already into drawing from ‘real life’ at that time and still am now. So I didn’t feel I belonged. I was never very good at facing a blank canvas, always needing a prompt in the way of an idea, a story or a visually arresting scene, very different from questions of surface treatment or personal, emotional states. Besides, my heart was never in oil painting, which requires a completely different way of thinking: mainly colour fields and colour relationships. Drawing – by which I mean hand-drawing, not electronic, software-generated drawing on an iPad for instance, because in drawing, the kind of paper the lines are applied to is also important – is the smaller-scale, sensuous art of expression through line, variable in thickness and colour intensity, often in black and white only and done with mainly dry media such as graphite pencils, charcoal and conté, or ink sometimes augmented with grey-scale or watercolour tints. The Netherlands, with its long history of masterful art practice, acknowledges the difference by according a special category to drawing, separate from painting, while here in North America, drawing is predominantly seen as ‘study,’ a prelude to painting. Paintings on canvas generate the big bucks in art galleries in this part of the world; drawings on paper, not so much. In the Netherlands, the drawing tradition we nowadays refer to as ‘urban sketching,’ the depiction of ‘real life on location’ was advanced in the 18th Century with the founding of studios for ‘Drawing Associations’ in various cities, such as Felix Meritis in Amsterdam, Kunstliefde in Utrecht and Pictura in Dordrecht. A resident of the latter city, Otto Dicke was a life-long member of Pictura and had his studio there. The Dordrechts Museum continues to emphasize the art of drawing in its exhibits and it’s a great way of showing the evolution of the city and its environs through the ages.

While the painters at school were left to ‘self-express’ without learning much about technique or ‘métier,’ I was fortunate that there were two teachers left at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rotterdam who taught the more traditional methods of drawing. One, Gijs Voskuyl (1915-2004), taught in the classic academic style – I even remember sketching white plaster replicas of Greek busts that were standing around in the classroom – but the other, more important teacher to me was Otto Dicke (1918 – 1984).

Not only was he an unbelievably accomplished sketcher, but he was gifted at gently, generously pointing out what to pay attention to while drawing a subject, be it a land- or cityscape, an animal or a person, without pushing us into one style or another. Interestingly, the director of the Art Academy at the time was a well-known and popular 7’ tall and skinny man called Pierre Janssen, who for many years had a talk show on TV where he would discuss works of art in language that a mainstream audience could understand; even when the masses had no interest in art, they would tune in by the millions because he was such a gifted and entertaining storyteller. We didn’t see much of him. I suspect being director of an art school was a sideline to him because he certainly didn’t impress on the curriculum that studying traditional images and techniques had value for young but lost art students. Even Picasso knew this. He purportedly said ‘before starting at abstract, ‘free’ composition and painting, you have to know what it is you want to become free of.’ Similar to Van Gogh and De Kooning among many other artists, as a young man Picasso started out producing conventional paintings as practiced in the day, which later came to benefit his more individualistic art. For some reason, this was no longer a truism once the ‘sixties came along, and I don’t know how it is in art schools nowadays.

First of all, there were the tools of the craft. Dicke showed us how he’d take an exacto knife and cut a nib at the end of a piece of ¼ inch thick bamboo stick. After ‘breaking it in’ for a time where the pen’s point dipped in India ink would adapt to the angle of his personal hand in drawing, this would be his favorite medium to use for on-location sketches. Using sepia ink, he produced the most wonderful, quick and loose sketches of Dutch polder landscapes, often in wintry moods, with a strong resemblance to Rembrandt’s style. Dicke loved the look of this flat land, especially where the horizon was still unobstructed by highrises, modern wind turbines or electricity towers. On weekends, you could often find him in his element, doing what he did best, in the Alblasserwaard polder just north of Dordrecht.

Dicke was the ‘urban sketcher’ par excellence, long before the term was coined. Practicing constantly his whole life, he knew how to portray, in deft strokes, the character of a town, a street full of people, a seasonal landscape, the graphic skeletons of trees in winter framing the buildings behind them.

He encouraged us to look, to really see. Don’t try to hide hands and feet when you do a life drawing from a model because you find them too complicated to draw: study them instead – look at them! Which was his gentle way of saying ‘don’t be so darned lazy, kids, don’t try to avoid the more difficult aspects of the trade.’ Understand how beautiful hands really are. Use of an eraser was discouraged. There were no right or wrong lines, you ‘felt’ your way through line, following the shapes you observed, correcting while drawing, constantly working on the entire image rather than focus on only a small part of it. No human anatomy lessons needed, just thorough looking at the ways the light falls over the body, how the clothes drape: this will tell you how a body ‘works.’ Much the same goes for drawing architecture. ‘Drawing is thinking,’ said the famous American graphic designer Milton Glaser. Draw the beauty around you because there’s much to learn about the world. Otto Dicke would take us to the local Zoo and start us off with the animals that sat still, such as crocodiles and sheep. Then we’d move on to more mobile subjects like tigers and birds to pick up speed of execution, to shed our inhibitions, increase our observational skills and exercise our eye-hand coordination. He’d make us try to recognize the essence of what made an antelope an antelope, not a cow, and once we understood the holistic premise of observing an animal’s characteristic nature by watching it move, we could draw it in any style, in any position. This could be applied to drawing people in the mall just the same. Building on technique and skill, to enable you to express the essence of a subject, create tension and strength of line and place the image on a page in an interesting way: Otto Dicke was a great teacher who was always drawing too, along with us in class, so he could better explain his decision-making process.

A highlight of my years at the Academy was a week-long study trip to the area of Giethoorn, guided by Dicke. It’s a watery place consisting of a number of islands in the reeds on the eastern edge of the Zuiderzee (in the Netherlands, we call this inland sea the Ijsselmeer since it was closed off by a dyke in the North), inaccessible to cars. What fun we had! I presume we did some drawings of those insanely cute, picturesque little houses in the fishermen’s villages around there, but I can’t remember and don’t seem to have them any more. But I do remember Dicke loving every minute of the intense contact with his fourteen young (18, 19? 21 years old at most), long-haired, boisterous and hard-partying students of a wide variety of backgrounds, enthusiastically taking photographs of proceedings inside our lodgings and out in the fields; his magnanimity the reason why we loved him right back.

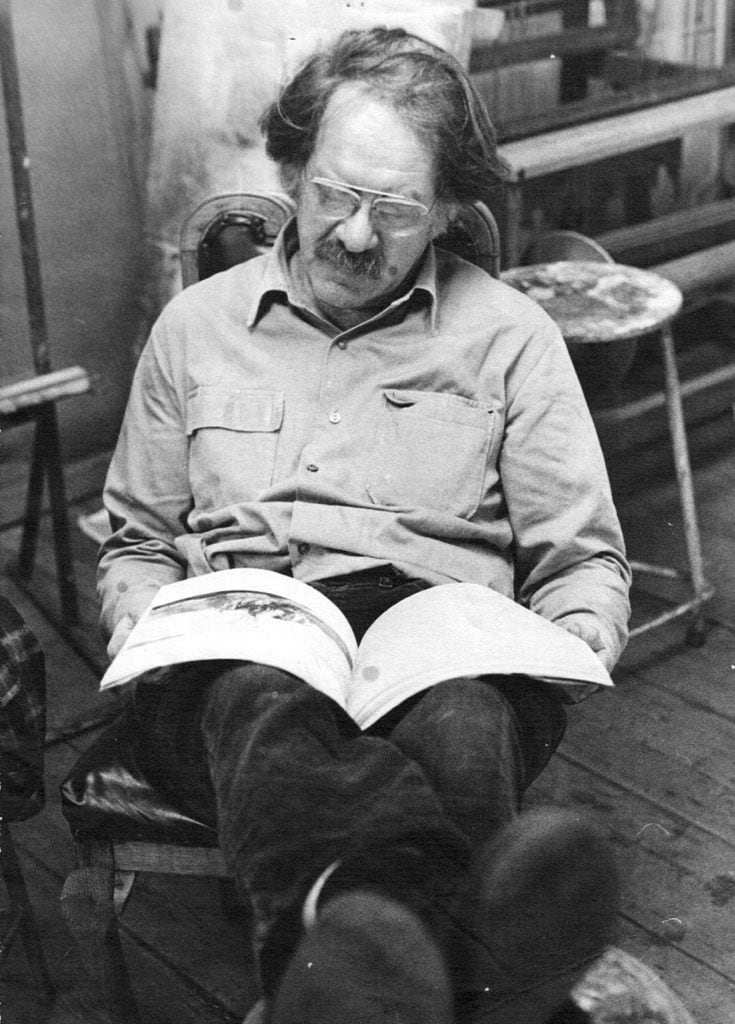

During one of my visits to the Netherlands, in 1984, I felt a strong wish to see him again after more than a decade, to show him some of my own work and pay my respects to him as a valued teacher. We met at his home in Dordrecht where we had an extensive conversation over tea and cookies, both very happy to connect again. He looked gaunt, had lost a lot of weight; he had been ill for a while, but still was the same attentive and kind, self-effacing Otto. He showed me a stack of his recent drawings after I expressed an interest in buying one. It’s in my living room here in Vancouver and I love it: it’s of one of Dicke’s favorite subjects of a typical Dutch vernacular polder farmhouse hugging a dyke, its lower part down below sea level, the top part climbing the dyke perhaps to save its inhabitants from rising water levels in times of crisis. The artist even managed to smuggle a little windmill into the background, so it doesn’t get more Dutch than this. To me, the emigrant, the drawing is a sweet reminder of my beloved home country, now that I live in a mountainous landscape that looks, sounds, smells and feels profoundly different.

Upon departure, Dicke gave me a little book of his drawings of the Zeeland city of Middelburg that had just been published and signed it for me, dedicating it (transl.) ‘to Mariken, for a wonderful memory of an afternoon in October – Otto, October 30, ’84. A mere five weeks after this visit, Otto Dicke died. His ‘bescheidenheid’ – modesty about his considerable accomplishments typified the man, right to the end.

It’s good to acknowledge the positive influence certain people had on your life, whether teachers, mentors, peers or friends, to let them know what they’ve meant to you and that you’re grateful for it. I’m so very happy I did, in dear Otto’s case, just in time.

(The next few posts in this series are about illustrators I admire and whose work influenced me, but didn’t know personally)

Ha Mariken, even beetje haastig, wel erg leuk wat je doet en mij stuurde.

ik ga er binnenkort echt even voor zitten en het lezen natuurlijk! Ben zelf hard aan het werk, veel op mn atelier op zuid. Tijdens coronatijd zeker een goeie tijd om er veel te zijn! ik loop vaak deels langs de maas en over de brug naar het atelier en ook op de terugweg varieer ik de routes. Erg prettig voor en na het werken, om te wandelen!

De fam en de kinderen nemen ook aandacht, er gebeurd veel. Maar op deze manier lukt het prima om de aandacht te verdelen. Betreft de kl kinderen,(5 stuks) hoeft er niet meer opgevangen te worden. De oudste is 17! de jongste 8 van mijn beide dochters. Verder blijf ik verslaafd aan het tekenen, wat ik overdag, tussendoor en s avonds doe.. Mooi dat jij ook van schrijven houdt, heerlijk om geconcentreerd te werken! We houden contact lieve Mariken! XX Thea (ik heb n slecht onderhouden website, goeie reden om er weer meer aandacht aan te schenken!)

For a non-artist this was a wonderful mini class on the skills needed for drawing — it allows me to appreciate what I am seeing even more.

Your tribute to Otto is very touching, and sage advice to acknowledge the significance of others.

And, I love your hippie hair!